Sex, Bronze, and The Human Figure:

An Introduction to The Art of Tony Paterson

Robert Paterson

Many people, myself included, consider my father, Tony Paterson, to be one of America’s greatest bronze sculptors, yet his work is still relatively unknown outside of a select group of artists, family members, and his former students. Essentially, his work has yet to be “discovered.” This is partly due to him not yielding to the trends of the day, which would have put him more squarely in the zeitgeist of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, but as I will describe later, it was also due to him not spending significant time promoting his work, especially later in his career.

I spent my childhood watching my father work and hundreds of hours over four decades speaking with him about his art, creativity, the art world, and life in general, so I have a unique window into his life and work.

Tony Paterson: Life Form Arch (bronze)

It is difficult to fathom how much my father created without seeing his works on display right in front of you. With hundreds of sculptures and two-dimensional works, his body of work is enormous, especially for a sculptor working primarily in bronze. The scope of his output and the diversity of his influences is breathtaking. Unlike many artists who spend a large part of their careers promoting themselves or their work, whether via social media, attending shows, dinners parties, and other social functions, my father was perfectly content to be reclusive: he worked on his art, taught, and spent time with his family. The socio-political environment of the art world was not appealing to him.

Other than his career as a professor, overseeing the University at Buffalo sculpture department for over thirty years, and founding the University at Buffalo Casting and Welding Institute, my dad spent most of his career focusing on his work and, to the dismay of his more academically-inclined colleagues, avoided administrating as much as possible. I believe that this is the main reason his output is so large. Quite simply, he worked on his art as much as he could until old age took over, and he could no longer sculpt.

My father’s work was defined by his experiences, history, tradition, and a desire to experiment and explore, although he rarely experimented for the sake of it. His experiments were almost always a means to an end. He was also influenced by the work of other artists, such as José Clemente Orozco, Vincent van Gogh, Alberto Giacometti, one of his former classmates, Jonathan Shahn, my mother, Eleanor Paterson (née Eleanor Cohen), and especially his former teacher and mentor, Harold Tovish, and Tovish’s wife, Marianna Pineda.

Categories

My father’s works may be broadly divided into the following categories, with a large amount of overlap:

The Human Figure

War and Peace

Confined Woman

Plants, Animals, and The Natural World

Portraits

Uncategorized Works

The Human Figure

My father was definitely fascinated by anatomy. He made casts of human skulls, skeleton-like figures, his own hands, and numerous portraits. He even sculpted what looks like a brain on a spinal column, which I always thought was curiously different than almost all of his other sculptures.

His earliest figurative sculptures are more Classical in nature and less abstract. These early works could be broadly categorized as The Human Figure since they are more literal representations of the human form.

War and Peace

My father served in the armed forces during the Korean War. Subsequently, with my mother, he was influenced by the Beat Generation and involved with the anti-war civil rights movement of the 1960s. All of these influences and experiences impacted him: not only in his early war-inspired works but also in his abstract figurative work. This is most clearly reflected in many of his early sculptures: Flayed Skull, Shelter, Threatening Bureaucrat, and so on. These works were overtly political, and he mostly moved away from this form of literal representation over time.

However, there are militaristic influences in at least a couple of my father’s later works. For example, there’s one sculpture, Female Form in Gun Turret Base, that includes a polished female form inside what seems like a rectangular gun turret, with the woman’s breasts jutting out like two oversized guns.

I often think that my father suffered from some form of PTSD. Had he served in the military later in life, this would probably have been diagnosed, and he would have been treated. Back in the 1950s, PTSD was not even recognized. I think his war-inspired works were a sort of therapy for him, a way to deal with and process the trauma he experienced during the war.

Confined Woman

As he mentions in his Statement, he titled his large collection of abstract works Confined Woman. Within this category, he incorporated a variety of forms, enclosures, and pedestals, again with quite a bit of overlap:

Abstract Figurative Forms (Female, Male, and Androgynous)

Venus Flytrap Enclosures

Hinged Enclosures

Suspension Enclosures

Box Enclosures

Totem Bases and Enclosures

Landscapes

Basic Pedestals

Plexiglass and Vacuum Form Light Boxes

Tony Paterson: Futuristic Torso (Plaster for Bronze)

Many of my father's figurative sculptures are so abstract that they can be viewed as androgynous, while some of his earlier human figures are more Classical in style and clearly female or male.

Although most of his works are, at first glance, inspired by the female form and he was deeply concerned with women's rights, he was also concerned with the human condition in a more universal way. He used the female form to represent humanity in a general way in almost all of his works, with a few works being outliers, like Life Form Arch, in which he was more explicit with regard to representing male anatomy.

If I had to single out what is most misunderstood about my father, it was that he was, in the truest sense, a feminist. He loved women. Not in a sexual way, although clearly, he was a very sexual person, but from an anatomical, physiological, and even psychological perspective. He believed in the equality of the sexes, and I think his choosing the female form was meant to be more representative than literal.

Herein lies a dichotomy, or even a duality: the bulk of his abstract output is entitled Confined Woman, yet he has repeatedly mentioned, both in our conversations and in his writings, the androgynous transgendered or transsexual nature of his work, particularly his figurative work.

On one hand, he believed that his work represented how much women have been held back throughout history, confined, and subjugated. My mother, Eleanor Paterson (née Eleanor Cohen, her professional and maiden name), was one of the original second-wave feminists and a brilliant artist in her own right, and I think he was very inspired by her. He watched her struggle as an artist in Buffalo, NY, a city where, in the 1960s and 1970s, it was difficult for female artists to be noticed, let alone celebrated. My mother never felt truly embraced as an artist in Buffalo, which deeply affected her and my father.

On the other hand, my father viewed society as holding the common person back, regardless of gender. He often reflected on this when we spoke about politics. He was an activist through and through and, after having served in the Korean War, a staunch pacifist. The combination of his early experiences and the time in history in which he lived shaped who he was as an artist, particularly with regard to his abstract work.

Plants, Animals, and The Natural World

Tony Paterson: Form Within a Form: Venus Flytrap (Bronze)

My father was fascinated with the natural world, and he found the perfect device to represent being trapped or confined in the Venus flytrap. He made numerous works in which polished, gemlike female forms are encased in spiky, darkly patinated Venus flytrap-looking enclosures.

He also sculpted birds and other animals. He was particularly fond of crabs and birds, as was my mother in her work. He sculpted a bronze bird and a Bird Planter, an almost two-dimensional bronze relief of a bird in flight, a terra cotta Bat, an early-period horse, and then his final, unfinished work, another horse. This is all in addition to his Birds in Flight Table. He also made numerous drawings and other two-dimensional works of animals, some of which were studies for the sculptures he would eventually cast.

Portraits

Both male and female portraiture is a very important part of my father’s output. This was partly due to the tradition of the medium (busts and heads are traditionally and typically cast in bronze), his own passion for this particular subject, and his lifelong career as a college professor. Teaching figurative sculpture involves learning how to create a head and a bust and my father would often work on his own sculptures while students worked on theirs, which allowed him to create his own work and demonstrate how it's done.

Broken down, his portraits generally fall into the following categories, again, with some overlap:

Prominent local figures

Other artists

Family members

Academics

Students

His portraits mostly consist of prominent local figures from the Buffalo, NY area, where he lived most of his life, but he also created a few portraits of other luminaries, such as composer Samuel Adler (one of my former music composition teachers who was at the Eastman School of Music and The Juilliard School). He also created portraits of his own family members, such as my mother, his sister Pat, and even me as a child. His portraits basically consisted of who he had access to during his career. Some of his portraits were sculpted while teaching at University at Buffalo, and he even sculpted a few portraits of his students.

He also made sculptures of other artists, such as local Buffalo artist Wesley Olmsted, who was related to Frederick Law Olmsted. He wasn’t pretentious about who he made portraits of; he was much more interested in their facial features: whether they had smooth skin or wrinkles, a broad or thin face, and so on.

One curious aside: he mainly sculpted the eyes to be smooth. Although he dug out the eyes' corneas a few times, he told me this was more of an experiment. Had he completed more portraits, he would have gone back to sculpting eyes more smoothly.

Uncategorized Works

I would be remiss not to mention my father’s works that defy easy categorization, mostly created early in his career but a few toward the end of his career. He made one sculpture entitled Bathers, another entitled Wheelchair, and a series of sculptures that seem to fit in a series with titles like Compassion, Compulsion, and Energy. In a way, these were the forerunners of his Confined Woman series and are clearly androgynous. He also made a small series of wooden frames with plexiglass panels, wooden bicycle-looking contraptions, and collage images of various types.

He has early drawings that were mostly still life studies, with images of dilapidated buildings in Cape Cod and other objects. This is in addition to the myriad of photographs he took throughout his career, which are more archival than artistic. Most of these un-categorized works are from his youth.

One particular work he created at the end of his career stands out, a piece he eventually titled Edison’s Ears, after a movement of a piece I composed called Sonata for Bassoon and Piano. My dad was very fond of this piece I composed. Since his sculpture is essentially a rectangular bronze form with a face embedded in the front and two open holes on either side for ears, he thought the title of my movement worked nicely for his piece, and I was honored that he wanted to use my title for his work. The title, Edison’s Ears, is inspired by a legendary story about the ear problems Thomas Edison suffered from throughout his childhood in Port Huron. According to this tale, when he was 15, a train accident further injured his ears. When he tried to jump on the moving train, the conductor grabbed him by his ears to help pull him up. The young Edison said he felt something snap inside his head and soon began to lose much of his hearing.

Influences and Mediums

Interchangeable Parts and Modular Design

My father was constantly experimenting and looking for ways to use forms in multiple ways. For example, he would often design various enclosures if he made multiple casts of a particular form, such as a skull or one of his polished female figures.

One example of this can be seen in the acrylic head used in his two Totem sculptures. Yet another example is his large-breasted female forms with as many as three bases or enclosures. These bases and enclosures created variety in his work, and the same piece can be displayed in multiple ways. He also designed a couple of Landscape sculptures to hold multiple polished forms.

An interesting aside: while growing up as a child, one of my favorite toys, and for my brother David as well, were sets of Legos and toys with interchangeable parts, such as Micronauts, which were space-age-looking robotic toys with articulated, interchangeable limbs and other parts. My dad would often sit with my brother and me, watching us, and join us on the floor to play with these toys. Whether he would have admitted it or not, I firmly believe that these toys had an effect on the playful, interchangeable, modular quality of many of his works.

Novelty

Various works incorporate novel or furniture-like effects, with lights, hinges, drawers, sheaths, enclosures, etc. One of his Totem sculptures, the Jarvis Memorial, includes a gold-plated sun as part of the design, a material that, to my knowledge, he only used once.

He even designed a small female form in which the breasts were attached by rubber bands and could be pulled out of two sockets on the chest and snapped back. I had endless fun playing with this sculpture as a child, maybe too much fun! He eventually removed the rubber bands and reworked this sculpture into a different form.

The novel aspects of his work tie into his playful and experimental nature. In a way, my father never lost his sense of childlike curiosity. His father died when he was a teenager, and his mother wasn't really available emotionally and had her own inner demons she was fighting with, so I think he was forced to grow up faster than normal.

Tactile Feel and Everyday Life

My father encouraged people to pick up his smaller pieces and hold them in their hands. He wasn't precious about letting people hold his polished pieces or opening his forms to see what was inside. He designed the smaller ones to be held.

One clear example is the hand-sized Form Within a Form, Dagger sculpture with finger indentations built right into the form, almost begging you to want to pick it up and hold it and perhaps gruesomely, in A Clockwork Orange sort of way, stab someone with it. I asked him many times about this work, and he mentioned to me the symbolism of how the human form can be deadly, and in this case, he encapsulated this notion in a very visceral way. My son Dylan recently took a look at this and said it reminded him of a shark tooth, which makes sense since around this time, my family used to vacation in Maine and Cape Cod, and I know my dad had a collection of shark teeth we found on these trips in his studio on a shelf. Perhaps a shark’s tooth also influenced how this form took shape.

Even his larger works often allude to being tactile or at least approachable. One of his largest works, Seated Form, almost implies that you should try to sit on it or view it as related to an everyday piece of furniture.

My father experimented with and actually designed a few sculptures that are literally furniture: his Birds in Flight Table, a bird form he derived from this, and even a couple of simple living room lamp posts that look like a daddy longlegs. He even made a sculpture out of terracotta meant to be used as a hanging planter.

I think part of the reason my father made sculptures that are meant to be held was his desire to connect, to allow his work to be utilized and integrated into everyday life. Ultimately, he wanted his work to be approachable, something a normal person in a home would enjoy showing off and having around, and not just something meant to be displayed under glass in a museum.

In a broader sense, I think this is related to confinement: my father wasn’t aggressive about finding a commercial gallery during his lifetime. Part of this was his being somewhat paranoid and not wanting to be taken advantage of financially, but another aspect was his wanting his work to be appreciated by individual art collectors.

To be clear: he definitely appreciated that he was in collections and shows and worked hard to have his work shown, but he was also into his work being collected an cherished by individuals.

Allusions to BDSM

At first glance, many people are convinced that my father was inspired by BDSM in his work when designing some of his more gruesome sculptures, especially the ones with spikes. I asked my father numerous times: is there something about him I didn't know? My dad was sexual, but he wasn't into BDSM, to my knowledge.

I think my father’s more BDSM-looking work was more aligned with imagery in stories by writers such as Edgar Alan Poe (a writer whose work he read to me at bedtime when I was little; no wonder I had nightmares as a child!). For him, it was more about people being proverbially held down and subjugated. I think the confusion lies in people conflating the overt sexuality in many of his pieces with the horrific, almost torturous, spiky nature of many of his bases and pedestals, but I think he was more concerned with confinement, the abstract notion of pain and the lack of control rather than anything representing personal experiences or overt sexuality.

Sense of Humor

Tony Paterson, Burning Man (Self Portrait) (Rice Paper)

My father definitely had a sense of humor, especially early in his career. You can see this in pieces such as his Totem, which has a secret drawer. I'll never forget the day he showed that to me when I was young. At the time, as an awkward teen, I was mortified. Later, as an adult, I was delighted. He designed this piece so that if you try to pull open the drawer, you can't. You first have to find the bronze latch on the back of the sculpture, and you can open the heavy drawer if you push the latch to the side. What you see next is meant to shock but also to make you laugh, which my father did when he showed it to me: you see a man's genitals embedded into the drawer. There's nothing about the exterior of this sculpture that would give away what's inside. On one level, this device plays into the idea of confinement, but this time focusing on the one aspect of the male physique that is most distinctly "masculine." On another level, my dad is being puckish, making a sculpture purely for fun to see people's reactions. What seems perfectly acceptable on the surface turns out to be slightly offensive, or at least shocking, if you are curious enough to open the drawer. My father once compared this to a puzzle box and Pandora's box. He viewed this as playful and fun, something to be cherished and not necessarily scorned, as if you are finding a hidden treasure. He also told me this was a statement against people covering up male or female genitals in public works. Curiosity will cause people to look and see what's inside the drawer, whether they want to or not.

Another instance of his dark humor can be found in his two-dimensional works. There is a life-size, early etching entitled Two Cockroaches he did when he was twenty-five. That anyone would want to display this prominently is hilarious: who wants to look at life-sized cockroaches? But as usual with my father, he pushed the boundaries of what’s acceptable.

There is one more humorous work that is one of my personal favorites: a work he later entitled Burning Man (Self Portrait) that shows his face burning off. My father was raised Catholic, and my mother has a theory that Catholicism influenced some of his works, so perhaps this was his version of burning in hell. For the record, he never once mentioned religion to me as an influence, but of course, if you dig deep enough, you can see various hints alluding to that. He took a trip in his youth to Mexico, where so much of the population is Roman Catholic, to study works by Mexican artists. In fact, he told me repeatedly over the years that he was an Atheist (and I am as well, so we bonded over that), so perhaps this particular self-portrait could be viewed as manifested Catholic guilt.

Commissions

Like most artists, my father completed a few commissioned works. Two of these are the Darwin Memorial, and Jarvis Memorial, which are within his series of Totem sculptures. Due to the sexual nature of most of his work, he was not commissioned as much as most artists, but I don’t think this bothered him too much, or at least as much as I thought it should have. He was commissioned for quite a few busts and heads, and I think we discussed many times that he could have done many more of these for money, especially for famous people, but he wasn’t very business-savvy when it came to encouraging people to commission him for portraits.

There were occasions when he created mock-ups of memorials that would never see the light of day. He once did a mock-up of a proposed sculpture in remembrance of slaves who had died. His proposal wasn't chosen, but the study still exists.

Materials and Experiments With Other Mediums

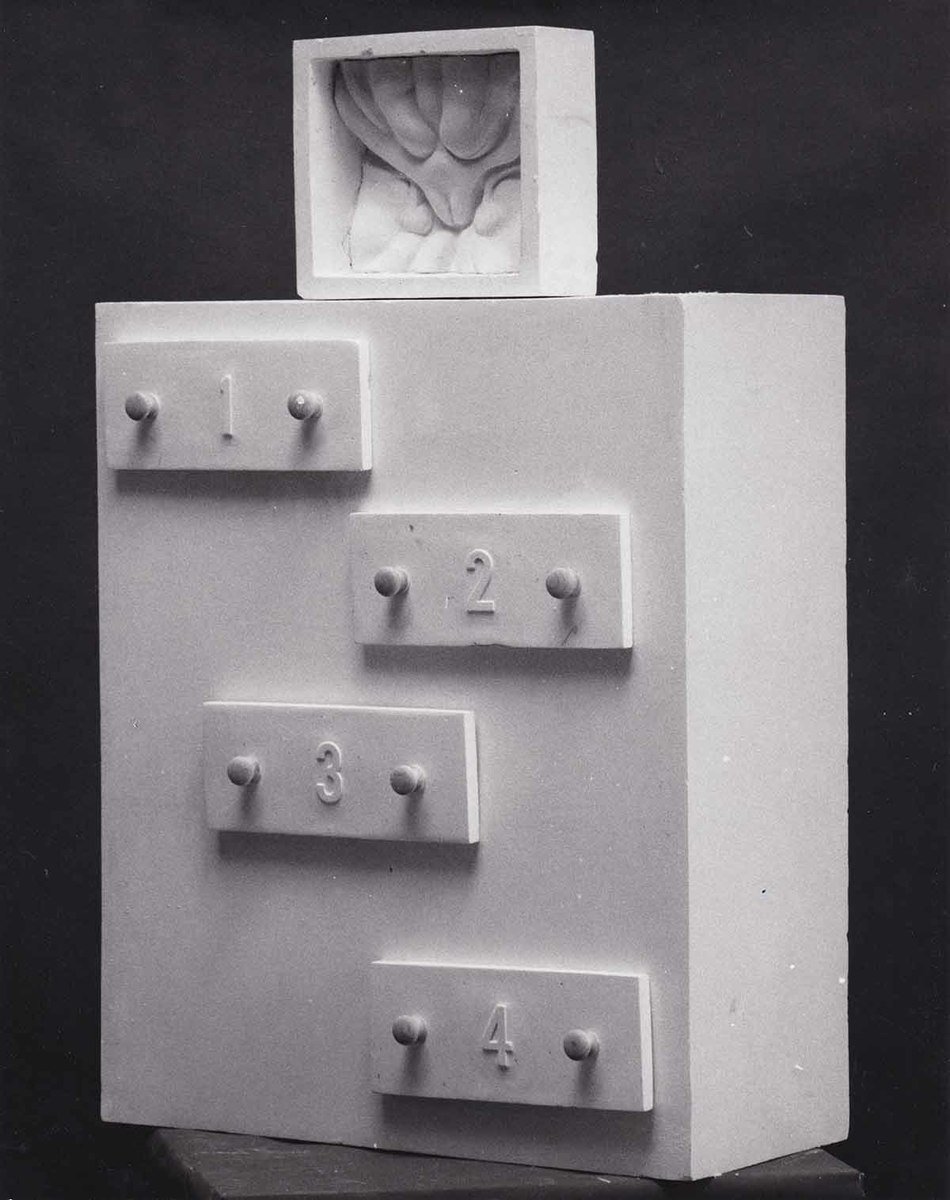

Tony Paterson: 1-2-3 (Bronze and Chrome Plated Base)

Although most of my father's works are bronze, he did experiment with other materials, especially early on. There is Positive/Negative, which has a bronze piece that swivels in a wood-frame pedestal. He also made sculptures out of plexiglass and vacuum forms, and still other sculptures where he experimented with techniques that he only used once. An example is 1-2-3, a work with three alien-looking heads mounted on a chrome-plated base.

Regarding his bronze sculptures, he sculpted figures in clay and Plasticine and used sheets of wax and heated tools to construct bases and other shapes. He made molds using plaster and Polysulfide (a.k.a. Black Tuffy). He used the lost wax process when casting.

My father often collected each alloy and made silicon bronze from scratch. Each alloy has a different color or characteristic, so some of his polished works may appear a bit lighter or darker.

For a brief moment in the late 1960s and early 1970s, he experimented with granite and marble but quickly abandoned these materials as a potential medium.

Light

Many of my father's works use light as a design element. His plexiglass/vacuum form box sculptures light up, and two of his Totem sculptures are lit from below, so the acrylic skulls glow in a sort of otherworldly way.

As a side note, he was grateful when one of his former students helped me update the antiquated lighting system in each sculpture with LED lights. The old lights flickered, barely worked, and were probably a fire hazard, so my father gave us permission to replace those, and he was very happy with the result. They have colored LED lights, and my son Dylan loved changing the colors when these sculptures that are currently displayed in our living room (red for Halloween!), and my father was humored by that but would sometimes roll his eyes. Even he had his limits.

Plasters

Tony Paterson: Acrylic Skull (Acrylic)

Tony Paterson: Female Form II (Plaster)

It never bothered my father too much that many of his larger works weren’t cast during his lifetime. I think he knew they would eventually be cast, but he didn’t have the money to cast these, and he was waiting for museums or private collectors to pay for casts.

However, I think he also liked how his sculptures looked like as plaster casts. My father thought they had their own special beauty, and he displayed many prominently throughout our house while I was growing up.

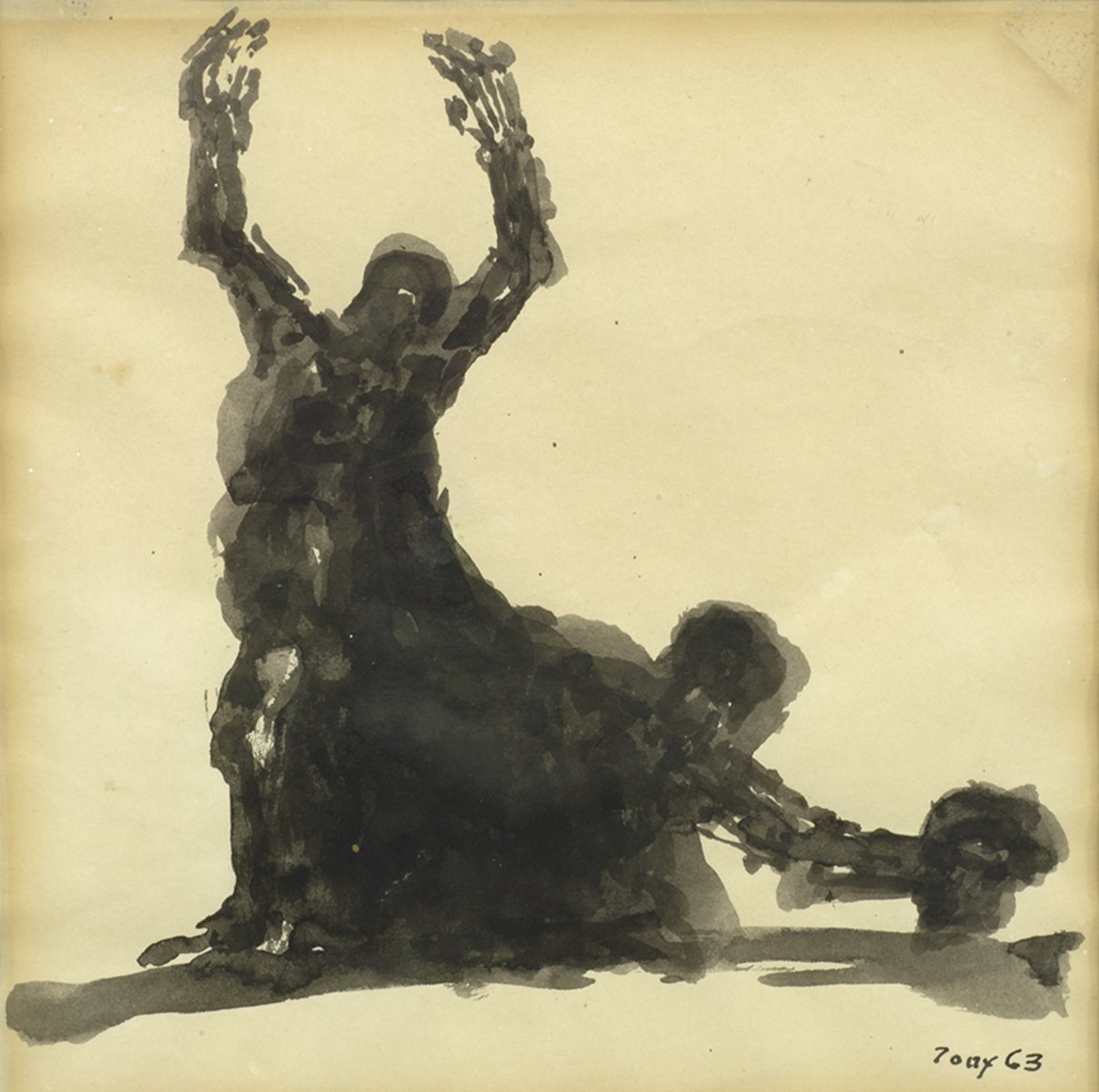

Studies

Before my father would create larger sculptures, he would often make two-dimensional studies or smaller versions. The different versions sometimes have slight variations, but they are more or less the same sculpture. He also made sketches or drawings prior to sculpting works, and he considered some of these sketches artworks rather than merely casual drawings to be filed away in a drawer.

Conclusion

Very few sculptors alive today, or at any point in history, created as many sculptures as my father, and especially without significant outside help. As mentioned earlier, I believe his work represents his personal life, experiences, and the human condition and is all at once profound, playful, and full of life. Despite the medium in which he chose to work, he was a true American rebel. Regardless of my being one of his sons, I strongly believe that his work will stand the test of time and be cherished far into the future.